A local man who almost died from anorexia as a teenager, but has now successfully recovered, gave a brutally honest account of his experiences to Year 9.

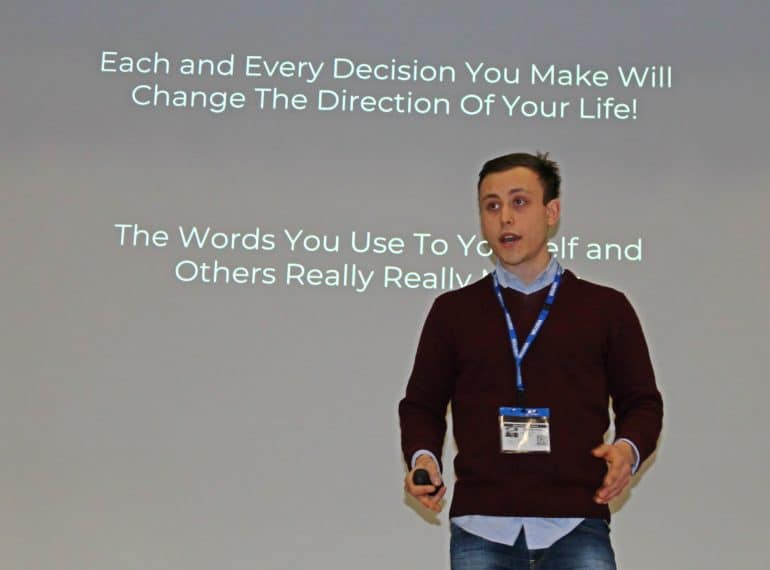

In his first-ever talk to a school audience, Jack Jacobs told the QE boys how the eating disorder almost claimed his life, before he took the important step of asking for help and then fought his way back to health.

Having decided he wanted to make a positive difference to others and help bring about positive change, he is now establishing a foundation, No Limits, to help people reach their full potential.

Headmaster Neil Enright said: “Jack’s was an inspiring story that clearly engaged the boys and got them thinking. It was shocking to hear how bad things got, but he showed how, with resilience and perseverance, even in the most trying of circumstances you can turn things around and make a success of yourself.”

Jack was invited to QE because of the general recognition that anorexia is a growing problem among teenage boys nationally, an increasing number of whom are afflicted by body-image issues that lead to them not eating properly or to over-exercising. Eating disorders and body dysmorphia are both addressed in QE’s new Mental Health and Wellbeing Policy.

Although not a former QE pupil, Jack comes from the local area. He told the Year 9 boys that despite playing rugby and cricket, he was a little “chubby” at school and that his fellow pupils and even some teachers indulged in name-calling and labelled him “fat”.

When he and his family moved to a new house on a long road, he took the opportunity to lose weight by running up and down that road. Determined to get in shape, he “ran and swam and then ran and swam”. He lost two-and-a-half stone in three months at the age of 14, yet the name-calling continued.

When he and his family moved to a new house on a long road, he took the opportunity to lose weight by running up and down that road. Determined to get in shape, he “ran and swam and then ran and swam”. He lost two-and-a-half stone in three months at the age of 14, yet the name-calling continued.

He therefore decided to run in a mini-marathon, driven on by teachers who had told him “you can’t run”. They were quickly proved wrong when he competed at Lea Valley with far more experienced runners and came in the top ten. He was scouted for a running club and emerged as a very strong runner, as evidenced by his 5k time of just 18 minutes.

He was, he told the boys, motivated by a desire to prove others wrong, so he started doing all the things people said he was not capable of doing. But he became fixated on fitness, food and counting calories. In short, he was starving himself.

Eventually Jack broke down and sought the assistance of others. “Asking for help is not weak, it’s strong – it shows you are self-aware, which is really important in life,” he told Year 9.

He ended up in hospital, with a heartbeat of 33 bpm and a blood pressure of 70/40 – readings that indicate a patient is close to death. The doctors took him up to another ward in the hospital where other teenagers were being fed by tubes because they wouldn’t eat. Seeing this, he made the decision to “grow”, that is, to get better.

As he began his recovery, he again had people telling him he could not do certain things, including doctors advising him not to take his GCSEs, but just to focus on eating. Jack feels the system treats people as “numbers”, rather than as individuals, but he believes “if you have self-respect, that is all you need and you can do it”.

A few months after being in hospital, he sat his GCSEs and achieved an A* grade, 8 As and a couple of Bs. “Don’t let people tell you that you can’t do things,” he said.

Jack stressed the merits of talking oneself into a better position: “What you say to yourself is what you become.” Having not been physically or mentally well enough to go anywhere for about a year, he then went to college. He started saying he had recovered (even doing so for a programme on ITV) – and then felt that he had to live up to this.