The family of Old Elizabethan helicopter pilot Roger Southgate have unearthed details of a heroic flight in hazardous conditions to rescue a comrade during some of the darkest days of Northern Ireland’s Troubles.

Major Roger Lee Southgate (OE 1958–1963), who died suddenly in April 2016 aged 70, served for 49 years as a soldier and then as a retired officer, spending most of that time in the Army Air Corps (AAC). He won his Air Force Medal (AFM) for an operation in 1974 and is believed to have been the first-ever AAC recipient of the award.

Major Roger Lee Southgate (OE 1958–1963), who died suddenly in April 2016 aged 70, served for 49 years as a soldier and then as a retired officer, spending most of that time in the Army Air Corps (AAC). He won his Air Force Medal (AFM) for an operation in 1974 and is believed to have been the first-ever AAC recipient of the award.

He was, his youngest son, Philip, says “a very humble, selfless and secretive person. He was well known, highly loved and also highly respected.”

Since his father passed away, Philip, who attended Bishop Wordsworth Grammar School in Salisbury, has been compiling his life history, including details of the episode in February 1974 that won him the medal.

Although the award was twice mentioned afterwards in the London Gazette – the British Government’s official journal of record – no details were given, and the family knew little about it until the day of his funeral. But, says Philip: “We managed to get his citation released from Whitehall, which it is very rare to obtain.”

The citation makes clear the extent of Roger’s heroism.

At 6pm on 27th February 1974, a request came into Roger’s unit for helicopter illumination of an area of the Sperrin Mountains near Londonderry, where two powerful command-detonated landmines had exploded on a country road, destroying two Land Rovers and injuring ten soldiers, one very seriously. This casualty was pinned beneath a Land Rover in a deep crater and was being fired on by the enemy in hiding. Darkness was falling, there was no moon, and the weather forecast was for haze and fog.

The citation explained that the Sioux helicopter Roger was flying had only limited night-flying capability, lacking full instrumentation and navigational aids. “Furthermore,” the report stated “it is easy to become disorientated at night in the Sioux, a condition where the pilot experiences an almost overpowering sensation that his aircraft is diving, spiralling or in other unusual attitudes. Because of this hazard, orders do not allow the Sioux to be flown at night unless the horizon is clearly visible.”

Roger knew of this, and knew, too, that it had been the cause of fatal accidents in the past. “Yet despite the lack of a visible horizon, coupled with a bad weather forecast, Southgate, knowing that a soldier’s life was at stake, agreed to fly the sortie and was accordingly authorised to do so,” the citation stated.

Roger knew of this, and knew, too, that it had been the cause of fatal accidents in the past. “Yet despite the lack of a visible horizon, coupled with a bad weather forecast, Southgate, knowing that a soldier’s life was at stake, agreed to fly the sortie and was accordingly authorised to do so,” the citation stated.

He flew straight to the site – the surrounding mountains, which he could not see, meant he could not circle the area in relative safety first – to find that the soldier had been freed from under the vehicle.

Roger now asked to be released, as the weather was deteriorating, but was asked to remain while the rest of the patrol were safely removed from the area. “This was because snipers were known to be in the area, and any localised light would draw fire. Knowing that his continued presence could prevent further casualties, Southgate decided to stay to see this operation through,” the citation continued.

This meant, as Philip points out, that he had to hover for over two hours, giving air support to the soldiers below whilst being continuously shot at by IRA snipers.

He was forced by the conditions to descend to just 150ft to provide illumination instead of the usual 1,000ft, which made the dazzling Nitesun beam reflect back into the helicopter’s bubble cab, adding to the difficulties imposed by the weight of the armour, of the Nitesun itself and of other fittings.

Eventually, with the patrol evacuated from the area, Roger was able to return to base safely, where he had to face the reaction of his superiors. “He was nearly court-martialled for this act of bravery, as he disobeyed orders from his commanding officer to return to base due to horrific weather conditions, being assisted by his navigator, who was only two weeks qualified. The commanding officer said it would either be a court martial or he would be awarded a medal!”

Eventually, with the patrol evacuated from the area, Roger was able to return to base safely, where he had to face the reaction of his superiors. “He was nearly court-martialled for this act of bravery, as he disobeyed orders from his commanding officer to return to base due to horrific weather conditions, being assisted by his navigator, who was only two weeks qualified. The commanding officer said it would either be a court martial or he would be awarded a medal!”

The citation concludes: “It is difficult to describe to those who do not fly helicopters the dangers inherent in this sortie and the degree of competence and courage which were necessary to make it a success. Sgt Southgate is an experienced Sioux pilot, and was prepared to experiment. The fact that he arrived at his destination and remained, despite appalling weather, to successfully complete an operation in conditions of considerable danger, which required the highest degree of skill, concentration and nerve, is to his great credit.”

Some months later, the AFM medal was duly bestowed on Roger by the Queen at Buckingham Palace, where he was accompanied by his father, Leslie, and wife, Norma.

As a boy, Roger lived with his father and mother (Joyce) and sister (Brenda) in a ground-floor council flat at the bottom of Cat Hill, East Barnet. Philip, who spent much of his childhood in Germany, where his father was stationed, remembers holidays spent with his grandparents at this flat, which still stands.

As a boy, Roger lived with his father and mother (Joyce) and sister (Brenda) in a ground-floor council flat at the bottom of Cat Hill, East Barnet. Philip, who spent much of his childhood in Germany, where his father was stationed, remembers holidays spent with his grandparents at this flat, which still stands.

His School report card from QE indicates that he was an accomplished sportsman – “useful [at] rugger & cricket”. He was “not at all a bad boy in character. Quite co-operative and willing…[with] a solid, straightforward manner”. Philip visited the School himself this summer, eager to see where his father had been educated.

One of the report’s final entries reveals that he had applied to join the Metropolitan Police but had been rejected because he was ¾ inch (1.9cm) too short.

Instead, he joined the Royal Military Police at the age of 16. He started flying training in 1968 and flew in the early years for Strategic Command in England, Denmark and Germany.

Instead, he joined the Royal Military Police at the age of 16. He started flying training in 1968 and flew in the early years for Strategic Command in England, Denmark and Germany.

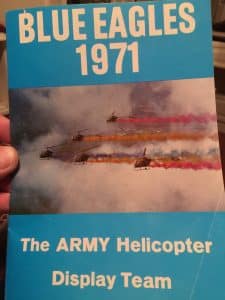

“By 20, he was one of the youngest pilots in the British army, by 25 he was in the first helicopter display team,” says Philip. He won his AFM at the age of 37.

Roger, later promoted to Major, was in charge of 7 Flight AAC in Berlin in the 1970s and of 654 Squadron in Detmold, in northern Germany, in the following decade, with most of the final years of his career spent at Middle Wallop, the Hampshire home of the AAC.

“He served a total of 39 years as a soldier and continued for another ten as a retired officer, based at the AAC headquarters in charge of pilot selection. Most of the modern-day pilots went through his courses, including HRH Prince Harry, and he was known by many more.”

Roger died from a sudden heart attack at the family home in Porton, Wiltshire. In addition to Philip, Roger is survived by Norma, his wife of 47 years, older son Richard, and grandsons Rohahn, aged three, and Lincoln, aged one.

Roger died from a sudden heart attack at the family home in Porton, Wiltshire. In addition to Philip, Roger is survived by Norma, his wife of 47 years, older son Richard, and grandsons Rohahn, aged three, and Lincoln, aged one.

More than 700 people attended his funeral, and those inside the church – and indeed spilling out of the rear doors – ranged from civilians to generals. The family received messages of condolence from all over the world, including one from Conservative peer Lord Glenarthur who knew and flew with Roger.

Major Roger Southgate AFM now rests in the military cemetery in Tidworth garrison in Wiltshire.