Pupils throughout the School celebrated Black History Month, participating in art and essay competitions, and learning together in student-led House assemblies.

Members of the club run by the School’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Ambassadors have been working on updating the EDI-related Perspective pages on the eQE portal (open to pupils and parents), as well as more generally building student leadership in areas such as combatting racism.

And Black History Month (BHM), with its theme of Saluting our Sisters, was also the focus of the latest edition of the Econobethan magazine.

Reflecting on how the last month had gone at QE, Assistant Head (Pupil Destinations) James Kane said: “I have been very pleased to see students from all year groups engaging positively with Black History Month, sharing their thoughts both during and after the House assemblies, and producing some excellent entries in our two competitions.”

Teams comprising House Captains and Form Representatives planned and delivered the six assemblies, which took Celebrating Black History Month as their theme.

“They spoke about what we can learn from the ways in which African, Asian and Caribbean people, and especially women, have overcome structural racism to achieve great things in different fields, linking these messages to anti-racism at QE and how we as a school, and as individuals, can be actively anti-racist and help to combat structural racism,” said Mr Kane.

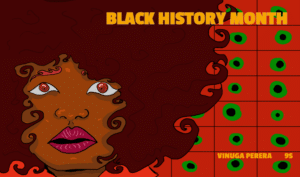

For the art competition, pupils were asked to submit BHM-related designs of a suitable size and shape for display as ‘wallpaper’ on computer monitors. The winner, chosen by Mr Kane and Lead Enrichment Tutor Kanak Shah, was Vinuga Perera, of Stapylton’s Year 9 form. His entry was displayed on all computers across QE during the month.

For the art competition, pupils were asked to submit BHM-related designs of a suitable size and shape for display as ‘wallpaper’ on computer monitors. The winner, chosen by Mr Kane and Lead Enrichment Tutor Kanak Shah, was Vinuga Perera, of Stapylton’s Year 9 form. His entry was displayed on all computers across QE during the month.

His design, described by Mr Kane as “strikingly bold” uses the colours of BHM – black, yellow, red and green – with black representing resilience; yellow, optimism and justice; red, blood, and green, Africa’s rich greenery and other natural resources.

Vinuga said: “I chose to put a person of colour in the foreground because I believe that BHM is recognising all the amazing achievements that black people have accomplished. The poster’s just really about representation of culture and people.”

More than 20 boys from Years 7 to 13 submitted essays for the competition, which was judged by a panel consisting of senior EDI Ambassadors including Vice Captains Arjun Patel and Indrajit Datta, as well as Riann Mehta and Roshan Arora.

The Upper School winner was Anish Kumar, of Year 13, with an essay entitled The Civil Rights Movement: Why it never ended, and why the 50s and 60s matter. The judges’ panel described it as “a very comprehensive analysis of civil rights movements; very sensitive to issues and appropriately expressed”.

Rishabh Satsangi, from Year 7, penned the Lower School’s winning entry, its title simply Subnormal. The judges’ notes appraised it as “beautifully written. A nice structure – thorough analysis of historical racism. The author has a clear vision of the future of more positive racial treatment within society.”

- Scroll down to read both essays.

The Civil Rights Movement: Why it never ended, and why the 50s and 60s matter

Anish Kumar

The plight of African-Americans in America is one that has become so ingrained in the cultural fabric of the nation that it is almost taken for granted how much of a disparity still exists not only in life outcomes but in the ability to exercise fundamental liberal rights that we may take for granted in the UK. Even in this country, to claim that society is now “post-racial” is to delude oneself into believing that a Britain where race and ethnicity still matter could ever truly be egalitarian. To understand the everyday inequalities faced by the Black community across the Atlantic, it is important to understand the social hierarchy built, first directly, and now indirectly upon racism. This essay will examine the experiences of African-Americans in America firstly through slavery and inferiority, followed by the century of Jim Crow and both de facto and de jure segregation, and then the Civil Rights Movement which reached its peak in the 1950s and 1960s, but never truly ended.

The historical oppression of an entire race within the US, while not unique globally, is the most significant of its kind within the developed world. An entire people with a near-universal shared common experience of the evils of slavery creates both a solidarity but a polarisation along racial lines unlike anywhere else, with the country displaying true heterogeneity. Racial division expresses itself in the United States not only politically (which alone is alarmingly stark), but also culturally and in the places where Americans live and work. Slavery was, for centuries, the “peculiar institution” that drove the Southern economy. The agrarian region largely lacked the North’s cities, industrial base and middle class, and remained dominated by the slave-owning planter class. It is clear here that African-Americans were brought across the Atlantic, against their will, to a nation where their economic destiny was preordained by a strict hierarchical system in which they were placed at the bottom not as workers but as property, dehumanised by not only society but by politics and the economy. The US Constitution, as written at the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention in 1787, was fundamentally enshrined as a racist document, defining slaves as 3/5 of a person as a “political compromise” between the north and south. African-Americans are dehumanised firstly in their economic status, but then again as bargaining chips. Indeed, the pre-Civil War court case Dred Scott v Sandford determined that African-Americans could not even be citizens in the country that was founded upon the liberal philosophies of life, liberty, and property, and the cruel reality is that within these three principles, only Whites and that too those of a particular class were seen as enjoying them in earnest and enslaved African-Americans were seen as only an economic tool, something to be fought for not as an identity but as a possession. The experiences of American African-Americans in the mid-19th century can be summarised by the Cornerstone Speech by Confederate Vice-President, Alexander H. Stephens:

We have settled, and, I trust, settled forever, the great question which was the prime cause of our separation from the United States: I mean the question of African Slavery.

The old [American] Constitution set out with a wrong idea on this subject; it was based upon an erroneous principle; it was founded upon the idea that African Slavery is wrong, and it looked forward to the ultimate extinction of that institution. But time has proved the error, and we have corrected it in the new Constitution.

We have based ours upon principle of the inequality of races, and the principle is spreading — it is becoming appreciated and better understood; and though there are many, even in the South, who are still in the shell upon this subject, yet the day is not far distant when it will be generally understood and appreciated…

[Our Government’s] foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based on this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth

The fundamental message here, that of the “inequality of the races”, is one that explains the plight of the pre-Civil War southern Black person. But this inferiority did not only apply to the enslaved Southern population, but also to the free people of the North. Racism was not a controversial belief system among 19th century American Whites, and it was Lincoln, who we see as a great emancipator today, who supported the American Colonisation Society’s efforts to resettle free African-Americans to a newly established colony rather than accept their integration into society. The active racism that has been experienced by the African-Americans in this era is a collective cultural trauma that still holds true today, and must always be kept in mind when arguments about “moving on” from the era are made. We can never truly move past such a deep scar on the collective imagination of an entire group, and the nature of race relations in the US is that we cannot move on from a system of oppression when the system is built on the foundation of racism.

The fight that the “redeemer” Whites of the South took to newly won Black freedoms after the Civil War and won is another in the long list of collective traumas that define modern heterogenous America. The Radical Republicans had in their ranks numerous elected, politically active African-Americans, popularly elected under the laws of the nation and under the principles that their people had never yet been able to enjoy the benefits of. There were no Black senators in the United States between 1881 (shortly after the end of Reconstruction) and 1967, and there were no Southern Black senators for 132 years after the Compromise of 1877 saw African-Americans once again sacrificed by Whites who sought to preserve their power. Throughout this era, and arguably even today, an entire group in society are routinely thrown under the bus for the political benefit of a class that, while no longer dehumanising them through a view of them as property, continues to do so by reducing them to statistics and acceptable “collateral damage” in power tussles.

Between the end of Reconstruction and the 1950s, it can hardly be said that the position of African-Americans improved to a dramatic degree, and the fact that race relations reached their nadir in the early 20th century teaches us the importance of civil rights today. The end of the military occupation of the South by Union troops meant that the Southern Democrats were able to establish control through violence and insurgency; groups like the KKK may seem a joke today but in their first iteration the Klan was a real threat to African-American suffrage, and in its second peak in the 1920s had significant influence, not only in the South but in northern states like Indiana. The black community in the United States experienced for a hundred years the injustices of Jim Crow: segregation, discrimination, disenfranchisement systematically by White Democrats who established a one-party state in the South. The near absence of any Republican politics meant that the real election was the selection of the Democratic nominee in the primary, which was limited only to Whites who could pass the local voting restriction laws, and therefore the interests of African-Americans were entirely excluded from government. While racism in early-to-mid 20th century America may have formed in the cultural imagination through southern legal segregation, the north remained de facto segregated, and in fact the Great Migration led in northern cities to racial tensions that were of a similar kind as seen in the South. Millions of African-Americans moved to escape the legally enforced inferiority they had assumed within the South, and found themselves in the industrial northern cities like Chicago and New York City. The continual theme of race relations in the time period covered here is that the white population has always resisted the progress of its African-American peers, and this manifested itself in the racial zoning laws of Chicago and Detroit, and the 1919 Chicago Race Riot which saw such destruction and brutality that it encouraged both groups to seek greater separation, even if it was not always strictly defined in law. The theme here, whether legally enforced or not, is that wherever those of darker complexion existed, their life was made poorer than it should have been by the conscious effort of white leaderships, whether that was for the reason of politics or prejudice. It was George Wallace who infamously said that when he tried to campaign on the issues of “roads and schools” hardly anyone listened, but when he began talking about “N——”, “the people] stamped the floor”. It was not a leadership acting on its own to suppress the black people while the whites watched on, rather it was a concerted effort by a broad white majority to suppress the rights of a minority, which has shaped the attitudes towards race relations held today, on both sides of the divide.

The Civil Rights Movement itself, while easy to view from across the Atlantic as having succeeded, was one settled not by politics, but rather by time. It is easy to forget that the end of Jim Crow was followed by the 1968 three-way election where the key theme was race and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F Kennedy. The Civil Rights Act 1964 was passed not along party lines, but along regional lines, and the vast majority of Senators and Representatives from the South, almost entirely Democrats, voted against the bill in both houses of Congress. The emancipation of African Americans in the South on legal lines was not immediate either, and the white elite, represented by the likes of Byrd, Thurmond (who had switched parties but not ideology), Wallace, Maddox and Faubus, remained firmly committed to their “Massive Resistance” campaign that had been the attitude towards integration throughout the Civil Rights Movement. A more romantic history of the time may be more inclined to look at the marches of King and the simple acts of defiance of Parks as the defining features of the campaign for rights, but it is, unfortunately, the case that the landmark Acts of the 1960s did not end racism, and, as with many “seminal” moments, only served to give the leadership an excuse to turn on the people they had just emancipated. Nixon and Wallace won 57% of the vote combined in 1968, campaigning implicitly and explicitly, respectively, appealing to the grievances of the White south. Humphrey, an old liberal, lost the election that went on to define the next five, with Nixon sweeping the South in 1972 on a Republican ticket that would have been consigned to single digit vote share just a few decades earlier, and the realignment of southern whites to the Republican party was one that took place on racial lines. The Civil Rights Acts and Voting Rights Act have spent the last five decades being chipped away by courts, and today southern states are strongly racially gerrymandered to the extent that when conservative Democrat John Bel Edwards won the Louisiana governor race in 2019, he won a majority of votes but won in only one congressional district out of the six. Civil Rights is portrayed by the education system as one of tension and resistance culminating in the acceptance of the three branches of government that change must finally come. This is true, to some degree: the judiciary passed the Brown decision unanimously, the legislature passed the Acts that ended legal Jim Crow laws entirely, and it was Kennedy and LBJ who pushed presidential support for desegregation. This would only ignore, however, the context of each of these decisions. Landmark moments were not so for their transformative effect on the status of African-Americans, but in how they catalysed resistance and support, often in equal measure, and despite obvious progress caused by the sacrifices that we focus on in our romanticised view of history, there is still so much to be done today.

In this sense, the Civil Rights movement never truly ended, or even begun. Shelby v Holder in 2013 struck down sections 4(b) and 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which has led to African-American disenfranchisement, while not on the same scale as the early 20th century, of the same political motivation. The Republican white Southern leadership is only following the inspiration of their Democratic predecessors, and the poll station closures and voter ID mandates in states like Texas and Georgia have had an unfortunate impact on the ease of voting for minorities, who heavily vote Democratic, especially in the South, and once again the white-majority governments have sacrificed the rights of black people for their own political objectives. The south is now so racially polarised that states in the South that do not contain large cities with enough liberal whites to swing elections (such as Georgia) can largely be electorally predicted along demographic lines. Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, are all states that have electoral margins close enough that split-ticket voting like that seen in the north prior to the 2010s would make their down-ballot races competitive, and yet the only one of the three that has elected a Democratic governor, senator or presidential candidate since Obama is Alabama, where Doug Jones won by less than 2% against a Republican candidate embroiled in allegations of improper sexual conduct with underage girls. America remains racially polarised, divided and often in active conflict, and the white grievance politics that carried the deep South for Wallace and Nixon in the 60s and 70s is not dissimilar from that which saw Southern and Appalachian whites finally abandon the Democrats after the election of the country’s first African-American president. Obama’s election was not the culmination of the Civil Rights movement, it was the reminder that racism never left and was merely buried by a leadership who felt they had “done enough”. The dog-whistle disparaging of those on “welfare” and those who “disturb law and order” is just the same attack on African-Americans as those made by the politicians of the last century, but disguised behind nicer terminology. Lee Atwater summed it up well in a 1981 interview:

Atwater: As to the whole Southern strategy that Harry Dent and others put together in 1968, opposition to the Voting Rights Act would have been a central part of keeping the South. Now [Reagan] doesn’t have to do that. All you have to do to keep the South is for Reagan to run in place on the issues he’s campaigned on since 1964 […] and that’s fiscal conservatism, balancing the budget, cut taxes, you know, the whole cluster…

Y’all don’t quote me on this. You start out in 1954 by saying, “N—–, N—–, N—–.” By 1968 you can’t say “n—–“—that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I’m not saying that. But I’m saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying, “We want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than “N—–, N—–.”

The emotional wedge issue of race that boiled to the surface with the Riots of the early 20th century during the time of Wilson and the 1950s and 60s in the era of King, were just the same as those which prompted the riots in Minneapolis after the police murder of George Floyd. Alabamian African-Americans have only this year been returned a second congressional district to elect a candidate of their choice, having been gerrymandered to just 14% of representation in the House while comprising 27% of the population. The 50s and 60s matter, but not because they represented the ushering in of a new, equal society, but because they remind us that the prejudiced majority in power continue to seek to restrict the liberties of the embattled minority. Black History Month may seem an afterthought, especially to those of us on this side of the Atlantic, but the average African-American has a lower life expectancy, educational outcome, and political representation when compared to their white peers, as we approach 2 months from the 60th anniversary of Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act. The neat period of history we call the “Civil Rights Movement” is better thought of as a particularly aggrieved era of the entire struggle for recognition and respect that the African-American minority has endured since they were first brought onto the shores of America against their will centuries ago. We must remember that the tyranny of the majority does not end, just because the majority concedes some of its unfairly gained power, and though events like the election of Obama in 2008 showed every black child that they can, and should, dream of anything and everything, the resistance that this incited reminds us that there is still so much progress to be achieved.

King once told us that he had a dream, one where his “four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but by the content of their character”. He told us that even after a Civil War, “a hundred years on, the Negro is still not free”. Sixty years on, they still are not free. Much like the parable of the Wise and Foolish Brothers, race relations in the United States are built on sand, and when the rain came down, the floods came, and the winds blew and beat upon it, great is its fall and descent into a chaos to which we have only responded by building upon those same shaky foundations. The Rights that have been violated for so long must be rebuilt, not by ignoring the foundational history of racism, but on the solid rock of the principle of equality that should guide us every day of our lives.

The fight continues to hold true the great foundational declaration of the world’s first liberal democracy:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness”.

It is the duty of all that we never halt the Movement that will secure for all, at last, the right to Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness that brings us the joys of humanity.

Subnormal – A government scandal that rocked the nation

Rishabh Satsangi

In 1948, the historic Empire Windrush arrived on British coasts, with hundreds of hopeful black Caribbean adults aboard in euphoria, entering – what they thought – was the mother nation. A couple of decades after this occurrence, the new generation created by these hard-working individuals trying to keep the nation afloat after WWII are facing severe discrimination despite the new laws introduced in 1948 British Nationality Act.

One of the main issues was the education they were receiving. West Indian parents saw education and schooling as a route to social mobility; they came here not for the financial benefits, but to ensure that the succeeding generations would prosper. During the 1960s, the Department of Education saw more and more black children entering schools, while more and more white parents began complaining about this. They suggested the arrival of them would hold back the future and potential of the current white generation – and the government agreed. The corrupt government of the time suggested that a meagre 30% of pupils should come from an immigrant background, taking them out of their own neighbourhood so they could be evenly distributed among schools. This example of institutional racism would wound the reputation of Britain as a welcoming country perpetually. Shortly after, scientific racism arose.

Many leading psychologists such as the German Hans Eysenck, falsely hypothesised that the average white child was born with more intelligence than an immigrant’s one. The influence of these people made the belief and racial discrimination spread like wildfire. So, the government created new educationally subnormal schools that were suited especially for students with learning difficulties and low academic ability. Majority of the time, the racist psychologists would create a test used to decipher who would need to go to an ESN school that required no such general knowledge. The average score was between 90 and 110; however, a survey showed that newly arrived West Indian children were scoring 70 on average. The government immediately seized the opportunity, bypassing any good logic. It was deduced that the immigrants were scoring low because of the cultural differences and traditions in the two places, but after they were accustomed to the British ways, they were scoring on a similar level to others.

However, all was not lost. Some adults were starting to believe that black children were being placed in these schools for no legitimate reason – one of them was a youth worker called Bernard Coard. Coard was not blind to this blatant racism, but he had no proof to directly accuse the government of this atrocious deed. An investigation began, starting at the Institute of Education of London University. It was there he uncovered the evidence that revealed a scandal that shocked the nation. He managed to carefully locate a report conducted by the Inner London Education Authority that explicitly revealed that “it is of considerable significance that heads thought 28% of their immigrant pupils wrongly placed compared with 7% of non-immigrant pupils”. Furthermore, it also explicitly stated that “the IQ distribution of the West Indian group is roughly the same as that of non-immigrants”. This was the undeniable confirmation that the fears many black parents were subject to was true. With a substantial amount of research, he published an influential book named, “How the West Indian child is made educationally sub-normal in the British school system”. Bernard’s book exposed the misgivings of the British school system and undermined the rumour that black children were born with less intelligence than white children. It was mainly addressed to the Caribbean community, pointing out that those in authority were not just doing something scandalously wrong, but more importantly, they knew it, and even more importantly, they were not providing any action on it.

The publishing of this book in May 1971 provided support for other debatable events, such as the New Cross house uprising in 1981 and others. Bernard’s book and this unfortunate debacle would have a major impact, for both the education of the developing black generation (the government decided to provide the book in teacher-training colleges shortly after) and the strenuous fight for equality in today’s modern society.