With next term’s examinations fast approaching, my colleagues and I have been further reflecting on questions of how young people study, of effective learning habits and of the best ways to revise.

A recent staff training day focused on how to improve information recall. Research has indicated that reading through notes and highlighting are poor revision strategies, popular as they are. As a general rule, the more active the strategy the better: in fact, even the simple act of reading aloud makes a significant difference to pupils’ ability to recall facts and ideas in an examination. Reading through notes infrequently followed by repeated testing is much better than infrequent tests interspersed by endlessly reading. Short but frequent periods of revision are more effective than one long ‘cramming’ session.

A recent staff training day focused on how to improve information recall. Research has indicated that reading through notes and highlighting are poor revision strategies, popular as they are. As a general rule, the more active the strategy the better: in fact, even the simple act of reading aloud makes a significant difference to pupils’ ability to recall facts and ideas in an examination. Reading through notes infrequently followed by repeated testing is much better than infrequent tests interspersed by endlessly reading. Short but frequent periods of revision are more effective than one long ‘cramming’ session.

We encourage boys to make intelligent use of technology in their study, but that technology can be a double-edged sword. It has been shown that the apparent efficiency of multi-tasking is illusory, because this habit does not take account of the way the brain actually works. Separate tasks, such as studying while trying to listen to something else, are handled by different circuits in the brain,  so if you pay more attention to one task for a moment, you are necessarily paying less attention to the other. Moreover, trying to learn new facts and ideas while multi-tasking can result in that information being sent to the wrong part of the brain, with the result that it is harder to retrieve later.

so if you pay more attention to one task for a moment, you are necessarily paying less attention to the other. Moreover, trying to learn new facts and ideas while multi-tasking can result in that information being sent to the wrong part of the brain, with the result that it is harder to retrieve later.

I know that, when not actually in lessons, many of our pupils, and perhaps some alumni, too, are always ‘plugged in’, smartphone, earbuds and social media at the ready. Some may even fear the prospect of boredom. While the urge to reflexively pick up your phone in moments of ‘downtime’ is understandable, in my view there is much to be said for embracing boredom. Spending time on your own with only your thoughts for company gives you the opportunity to play them out in your head, to explore those ‘new ideas and new solutions’ – concepts not yet sufficiently developed to be shared with others – that form part of free-thinking scholarship. Advances in neuroscience have confirmed physiologically that allowing the mind to wander can engender deep insights and strategic clarity, while also enhancing mental health. The development of such habits accords well with our mission’s aim of “promoting boys’ general wellbeing and their enjoyment of learning, rewarding effort and celebrating success”.

Periods of reflection (‘daydreaming’) can absolutely be productive. As I told guests at our Senior Awards Evening, where we welcomed as our guest of honour, Professor Michael Arthur, President and Provost of University College London: “Creativity cannot be scheduled, nor inventiveness timetabled.” Richard Feynman came up with his Nobel Prize-winning ideas about quantum electrodynamics by reflecting on a peculiar hobby of his — spinning a plate on his finger. And without a time of solitary reflection, we might never have had Harry Potter. J K Rowling traces the boy wizard’s genesis back to a railway journey from Manchester to London which she spent alone, without smartphone or even pen and paper.

Periods of reflection (‘daydreaming’) can absolutely be productive. As I told guests at our Senior Awards Evening, where we welcomed as our guest of honour, Professor Michael Arthur, President and Provost of University College London: “Creativity cannot be scheduled, nor inventiveness timetabled.” Richard Feynman came up with his Nobel Prize-winning ideas about quantum electrodynamics by reflecting on a peculiar hobby of his — spinning a plate on his finger. And without a time of solitary reflection, we might never have had Harry Potter. J K Rowling traces the boy wizard’s genesis back to a railway journey from Manchester to London which she spent alone, without smartphone or even pen and paper.

At other times, creativity can be stimulated by articulating one’s thoughts and discussing them with others. Here, the time that boys spend in School is important, and QE offers them just the right sort of interlocutors – a combination of equally able and interested peers, together with staff who have deep knowledge, expertise and a well-developed interest in the subjects they teach.

I n this age of always-on technology and Google, some question whether we need to memorise facts at all. A pragmatic answer is that effective recall of information has become more important for schools because of recent educational reforms and the return to linear assessments and final examinations. Our senior boys simply must develop the skills of retaining information. One way of achieving this is to train the brain through enjoyable but stretching extra-curricular activity: the learning of lines required for drama productions such as this term’s Lord of the Flies is a good example. But beyond the drive for examination success, there are deeper reasons for our insistence on the importance of knowledge acquisition. In order to think profoundly about ideas, it is first necessary to have certain content securely lodged within your brain.

n this age of always-on technology and Google, some question whether we need to memorise facts at all. A pragmatic answer is that effective recall of information has become more important for schools because of recent educational reforms and the return to linear assessments and final examinations. Our senior boys simply must develop the skills of retaining information. One way of achieving this is to train the brain through enjoyable but stretching extra-curricular activity: the learning of lines required for drama productions such as this term’s Lord of the Flies is a good example. But beyond the drive for examination success, there are deeper reasons for our insistence on the importance of knowledge acquisition. In order to think profoundly about ideas, it is first necessary to have certain content securely lodged within your brain.

Moreover, we are in the business here of nurturing and equipping young men who will in the future take up places as leaders in society nationally and internationally. And, simply put, to be a sophisticated adult of that ilk, there is ‘stuff’ you need to know. To this end, we have been turning our attention to the curriculum in the Lower School, asking ourselves if we have got the content right. Cognisant of the fact that boys will inevitably study some subjects for only three years, we are considering what cultural capital every student of Queen Elizabeth’s School should acquire as a minimum. For example, after nine terms of Music lessons, will all pupils be able to appreciate the different genres?

This term, I have enjoyed opportunities to greet old boys who have returned to the School to engage with our current pupils. Most recently, there was Hemang Hirani (OE 2008–2015), who came in to lead a discussion session with a select group of Year 12 geographers. Hemang, who is now a Private Banking Executive at Barclays, studied Geography and Economics at the LSE. His visit was a valuable example of an important aspect of the support we seek to offer pupils – helping stretch the older boys academically by giving them an insight into, and a taster of, university-level material and discussion.

Earlier, we had a return visit from Nick Millet (OE 2001–2008), who spoke to boys in the middle years about his work with refugees, reminding us that although the international migrant crisis in southern Europe may largely have disappeared from the headlines in recent months, an immense humanitarian challenge remains. Nick put his career as a management consultant on hold to co-found the charitable organisation Refugee Education Chios, which provides education, support and training for teenagers and young adults living on the Greek island of Chios, which became a de facto detention centre after the 2016 EU-Turkey agreement.

The ethic of service and of giving something back to society, which Nick’s work reflects, is seen in the endeavours of many younger alumni. Elsewhere in this newsletter you can ready about the fundraising project being undertaken by three OE students at St George’s University Medical School, namely Raahul Niranchanan, Vipushan Konesalingam and Athithyan Vijayathasan.

On the School website, we also reported recently on the efforts of Oxford undergraduates Conor Mellon and Rohan Radia (both OE 2010–2017), who raised £1,800 for a range of charities when they took part in the Oxford RAG’s annual jailbreak ‘run’ and, I understand, successfully reached Amsterdam.

On the School website, we also reported recently on the efforts of Oxford undergraduates Conor Mellon and Rohan Radia (both OE 2010–2017), who raised £1,800 for a range of charities when they took part in the Oxford RAG’s annual jailbreak ‘run’ and, I understand, successfully reached Amsterdam.

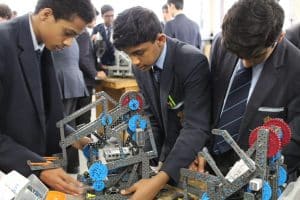

Our young roboteers are currently preparing to go even further afield after being hugely successful in national competitions: I spent a happy lunchtime congratulating around 30 of them as they look forward to going to this year’s international VEX Robotics international finals in Kentucky, from where, of course, QE emerged with a world championship title last year.

It was good, too, to see so many members of the Elizabethan community, including alumni, turning out for the Rugby Sevens.

My best wishes to all Old Elizabethans,

Neil Enright,

Headmaster